The Harry Ransom Center has been conducting a survey of medieval manuscript fragments as binder’s waste in their book collection since 2011. In 2012 we began crowdsourcing the identification of those fragments. Below is the transcript of a recent talk I gave on the project at the Society of Southwest Archivists Annual Meeting in Austin. Please note that some of the stats have changed since the talk was given.

“Reduce, Re-Use, Recycle. Any responsible modern citizen is familiar with this concept. The idea is not new.

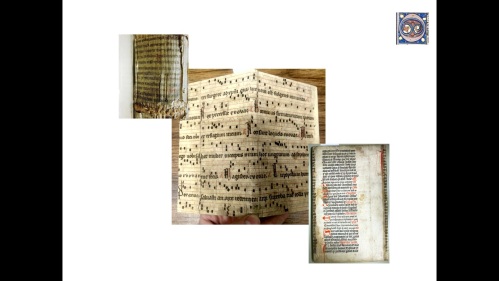

As handwritten books of the Middle Ages became outdated, bookbinders of the early modern period would cut out their sturdy parchment leaves and recycle those leaves as covers, pastedowns, spine-linings or gathering reinforcements in new, “cutting edge printed books.” The practice of cutting up unwanted and out-dated manuscripts in order to re-use their parchment leaves as binding waste lasted until around 1650 when the sources finally began to dry up. Today a large number of medieval manuscripts are dispersed throughout the world’s great libraries within the bindings of early printed books.

Historically speaking medieval manuscript fragments bound into books have received less descriptive attention than complete manuscript codices. Catalogers may note them as “manuscript waste” in the MARC record for the book in which they are bound, but this is typically it. Institutions rarely have the time or resources to provide transcriptions, highly detailed descriptions, and other extensive metadata. But since many collections of complete medieval codices have now been digitized, scholars are increasingly turning their attention to what I like to call the “orphans of the manuscript world.”

A little over two years ago the Harry Ransom Center began a survey of medieval manuscript waste in the printed book collection. Given my background in manuscript studies I was obviously excited about the project. But identifying the texts on these fragments can be challenging even for the most skilled medieval manuscript specialist and I had a number of other projects which took immediate priority over this one.

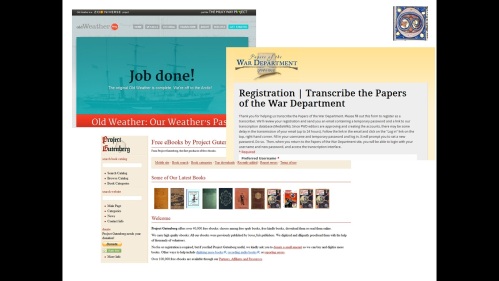

I was familiar with the successes of several institutional crowdsourced transcription projects and the collaborative identification of historic photographs on Flickr by amateur enthusiasts.

And it was the latter that got me wondering if something similar might be done with medieval binder’s waste. Although the work is highly specialized, we figured surely there were enough folks out there with some skill in Latin Paleography that we might actually be able to identify most of these objects relatively quickly. Sure, we had the option of adopting vague descriptive language or simply not identifying any of the really difficult texts, but I was tantalized by the possibilities of crowdsourcing and collaborative description and this seemed like a good excuse to try it out.

Creation of Flickr account

Having received approval from the proper authorities, early in June of 2012, we began taking images with a point and shoot camera (and later a smart phone with an 8-mega-pixel camera) and posting them on a Flickr pro account.

Creation of Facebook account

We also created a Facebook account with the same name and a banner image of one of our more attractive fragments so that we could post notifications about new images, interesting problems, and project milestones for followers. We currently have 131 “likes” on Facebook. I’ll admit that at least a 3rd of those are probably my friends. The rest tend to be from Europe.

Creation of Twitter account

I initially resisted Twitter since I was the one managing the accounts and it seemed a bit overwhelming, but after presenting our work at a conference in late October of 2012, I was convinced by several prominent manuscript scholars to go for it. In order to help unify our presence online, we adopted an icon of an illuminated initial to use across all accounts. We now have around 241 Twitter followers. The way we got our followers was by following libraries with large manuscript collections and medievalists with lots of followers! We have noticed a direct correlation between twitter posts and increased views on our site. There’s no question that you will see increased traffic if you post photos regularly on Twitter and Facebook.

Initial exploratory phase

Once we had 34 images posted on Flickr we made an announcement on the rare-book list-serve Ex-Libris. Our Flickr site received 659 views and 4 potential identifications in the first couple of days. The first serious increase in traffic came when the Ransom Center ran a story about our project on its blog Cultural Compass late in July which brought us almost immediately up to 2,422 total views and around 16 different contributions. The next big jump in traffic came in mid-August 2012 after posting an announcement to the Early Book Society list-serve which brought us to 6,828 all-time views and several more contributions.

SLU conference

By the time we finished posting images of all 79 known fragments on October 5th 2012 the site had received over 14,000 views and 21 of the fragments had been identified.

Intensification of search

After finding and posting images of all known fragments we conducted a shelf-search through our minimally cataloged collections of books printed before 1700 and managed to increase the total number of distinct fragments in bindings from 79 to 128.

Creations of sets

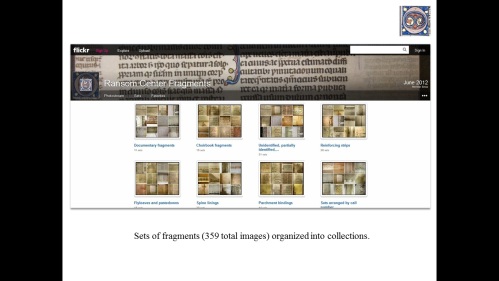

Using the “sets” feature on Flickr we arranged our photos into groupings of images of fragments from individual bindings. So although there are now 119 sets, some of those sets include fragments that originate from more than one manuscript.

Collections

Once we had had all the sets created we arranged them by the call number of the books in which the fragments were bound. We also used the “Collections” feature which allows you to arrange sets into groups to create a few curated sets of photos organized by different types of binder’s waste. Really the possibilities are endless.

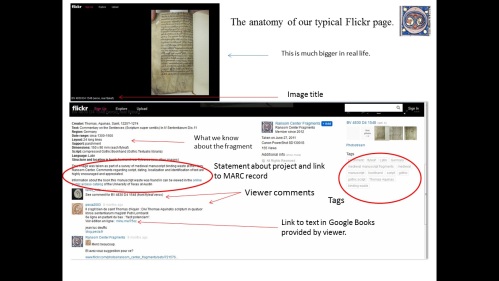

Anatomy of a Flickr page

Here’s an example of a typical page. Flickr underwent a major site redesign just this past Tuesday and the images are now displayed in their original resolution which is fantastic for viewing small scripts.

Each photo has a title with the call number of the book and the physical location of the fragment within the book.

Metadata for the photo is included just below the image and it includes just the basic information about the fragment so that viewers can get a sense of what we do and do not know.

We also utilize the tag feature and basically use uncontrolled vocabulary. More tags generally mean more views. The of course it’s no guarantee.

Below that is a statement about the project and a link to the MARC record for the book. We are also creating links within the marc record to the Flickr image so that it’s a two-way street for traffic. I’m hoping that there’s a way for us to ultimately track traffic from Flickr to our Online Public Access Catalog via these links.

And finally, below this metadata field are viewer comments.

Stats

So to summarize our results: As of yesterday our Flickr site has received over 26,445 views since June of 2012. 122 out of 359 images have received comments.

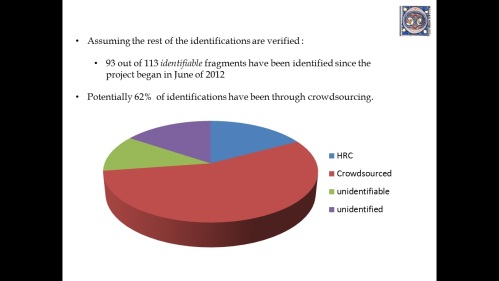

Viewers have potentially identified 71 out of 128 distinct texts. 15 fragments are not really identifiable due to loss of text or lack of visibility. And I have identified 22 fragments myself thus far.

This means that (assuming the rest of the identifications are verified) 93 out of 113 identifiable fragments have been identified since June of 2012 and 62% of these have occurred through crowdsourcing.

Methods of searching

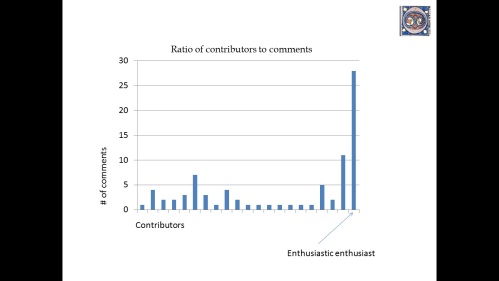

A closer look at the contributors confirms what others have learned from crowdsourcing projects, which is that a majority of contributions are made by a hand-full of “well-informed enthusiasts.” In our case, one lawyer and rare book enthusiast with a tremendous drive has made the majority of identifications. So far we have 21 contributors and out of those 21 this person has commented on 28 sets whereas the rest average around 3. We don’t know a whole lot about our contributors yet, since Flickr hides that information, but contributors with known credentials tend to provide information via e-mail rather than creating an account and posting directly on Flickr.

It’s important to note that most contributions involved identifications of fragments via text-string searches in Google Books. A couple things need to be said about this. First, it’s amazing what you can do with Google Books. When I started training in manuscript studies about 7 years ago, the primary method of identifying texts was to use good old fashioned off the shelf reference sources. This usually required an excellent memory, access to bibliographies, and a great library. Google Books now truncates quite a bit of this work. The main problem with some attributions is that just because a string of script on a fragment matches a string of text in Google Books doesn’t mean it is the exact same text, or that the digitized book represents the best edition. But I’ve found that in most cases this “Googling” method allows you to at least get a reference point.

So far we’ve reviewed 89 of the 128 fragments and have only found 1 (possibly 2) miss-identifications for fragments identified through crowdsourcing. I think this is pretty amazing. So far no one has attempted to do anything malicious (knock on wood) or made any wildly wrong identifications

Database entry

Once we have finished verifying all contributions we will transfer our metadata from Flickr to our database of medieval and early modern manuscripts on the Ransom Center website. The images will stay on Flickr, but we haven’t decided what to do about the metadata since the authoritative information will be on our website. We would certainly like to keep the conversation going and encourage viewers to continue commenting and sharing insights.

Bigger picture–what’s next

So what exactly do our numbers tell us? Well, I’d like to think it shows that you can indeed crowdsource the arcane. Although the ratio of comments to views has been fairly low, from the perspective of access, this project has been a success especially given that this is an extremely niche subject. Whether or not the project is a success purely in terms of scholarship remains to be seen.

Flickr disclaimer

I want to assure you that this is not a wholesale endorsement of Flickr. It has some major drawbacks. For instance, there is no true zoom feature and large leaves with small dense script are virtually unworkable. Users can’t view and comment on multiple images at the same time and it’s also an awkward platform for creating transcriptions—the comments section is usually too far below the image to transcribe while looking at the text. Finally, Flickr should not be used as a repository for long term preservation of your digital photos since we just don’t know how long they’ll be around or how they will change.

One way I like to think of it is as a FREE collaborative brainstorming sketchpad or drawing board for your own future professional platform/ website.

In conclusion, I do think it’s important to maintain the integrity of our profession by not wholesale farming-out descriptive work to just anybody, but I’d like to suggest that there is room for both the amateur and the expert in parallel forums. At the very least, the comments posted on our Flickr site create a record of interaction with our holdings from the outside that’s generally not possible with most institutional platforms.

The Ransom Center Fragments Flickr site no doubt will ultimately vanish into the mists of this digital dark age. But the project never set out to provide a monolithic body of inerrant data. All collaborative projects like this, in my opinion, are more about the process than the final product. There is enormous potential for discovery within and between different knowledge communities right now and it’s fair to say that open-ended crowdsourcing can exist alongside professionally vetted, sustainable institutional projects. Let’s go crowdsource the arcane.”

Postscript (things I would like to have included in the talk)

Below are a few of the more significant lessons learned in this project.

- Collaborative identification of texts doesn’t necessarily save you time (you still have to verify).

- Do utilize list-serves, they will likely be your largest source of viewers.

- Incorporate blog posts and try to get publicity through bigger websites/institutions.

- It’s a good idea to try and get your local user group behind you as quickly as possible.

- Make physical connections with your local user group as soon as possible.

- It’s probably best to try and facilitate comments by responding right away instead of just observing and then getting back to them later—don’t assume others will chime in.

- Some contributors provided extremely detailed paleographic assessments (sometimes of marginal inscriptions) without trying to identify the text—be prepared for unexpected observations.

- One additional advantage to photo-documentation is reduced handling when describing.

- I’m pretty sure some fragments were viewed simply because the photos looked interesting.